The Unwilling Architects Initiative

Who “built” Victoria Mansion? We are familiar with Henry Austin, the architect, Gustave Herter and Giuseppe Guidicini, the interior designers, and of course Ruggles and Olive Morse, who commissioned the house and its contents. Ruggles Morse amassed a fortune as a proprietor of luxury hotels, in part at the expense of enslaved labor. Ongoing research has led us to discover more than two dozen Black and mixed-race individuals who had been purchased and/or sold by the Morses. Through our ongoing Unwilling Architects initiative, we endeavor to learn more about and interpret the lives of the individuals who were impacted by the Morses’ decisions and who unwillingly assisted in underwriting the construction of this palatial Portland mansion.

About the Initiative

The Unwilling Architects initiative, launched in 2021, aims to expand our knowledge of the Black and mixed-race individuals who played an unwilling part in the rapid accumulation of the Morses’ fortune, which underwrote the construction of Victoria Mansion. Though this work will be ongoing, an initial round of research has already allowed us to begin updating and expanding our interpretive materials and educational programming.

Funding for The Unwilling Architects initiative has been provided by The Maine Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

During the initial phase of this initiative, we have been excited and honored to work with Anisa Khadraoui as a DEI consultant. Ms. Khadraoui has worked previously with the Abyssinian Meetinghouse in Portland, and in DEI with her alma mater Brown University. Her consultancy on this project has helped us shape the goals and products of this ongoing work.

The stories of the Black and mixed-race individuals and families impacted by the Morses are significant parts of the history of the Mansion, as well as the history of the United States as a whole. Where many of the historically Black burial grounds in Louisiana having been lost to natural causes and human influence, we endeavor to do what we can to restore the stories of these individuals to history. It is also our aim to accurately place Victoria Mansion in the context of 19th century Portland, a community that flourished financially with direct ties to the slave economy, notwithstanding a ban on enslaved labor in the Northern states. This initiative reflects our collective commitment to be forthright about the Morses’ role in the institution of slavery in the 19th century.

Individuals Enslaved by the Morses in New Orleans

Robert Johnson

Joshua

Louise

Jim, Louise’s son, age 6 in 1848

Hagar

Jefferson, Hagar’s son, age 7 in 1848

A 16-year-old girl, whose name is not yet known

Milly

Taylor

Hypolite

John, age 25 in 1853

John, age 16 in 1853

Charles, age 15 in 1853

Addison Hawkins

Alexis

Charles, age 14 in 1854

Henriette

Abraham

Joe, age 17 in 1858

Alonzo, Flora’s son, age 9 in 1859

Henry, Flora’s son, age 7 in 1859

Hailly, Flora’s daughter, age 4 in 1859

Henry, age 27 in 1860

Narratives for many of the individuals named above are in progress and will be available to read on this webpage soon.

Biographies

David Wilson

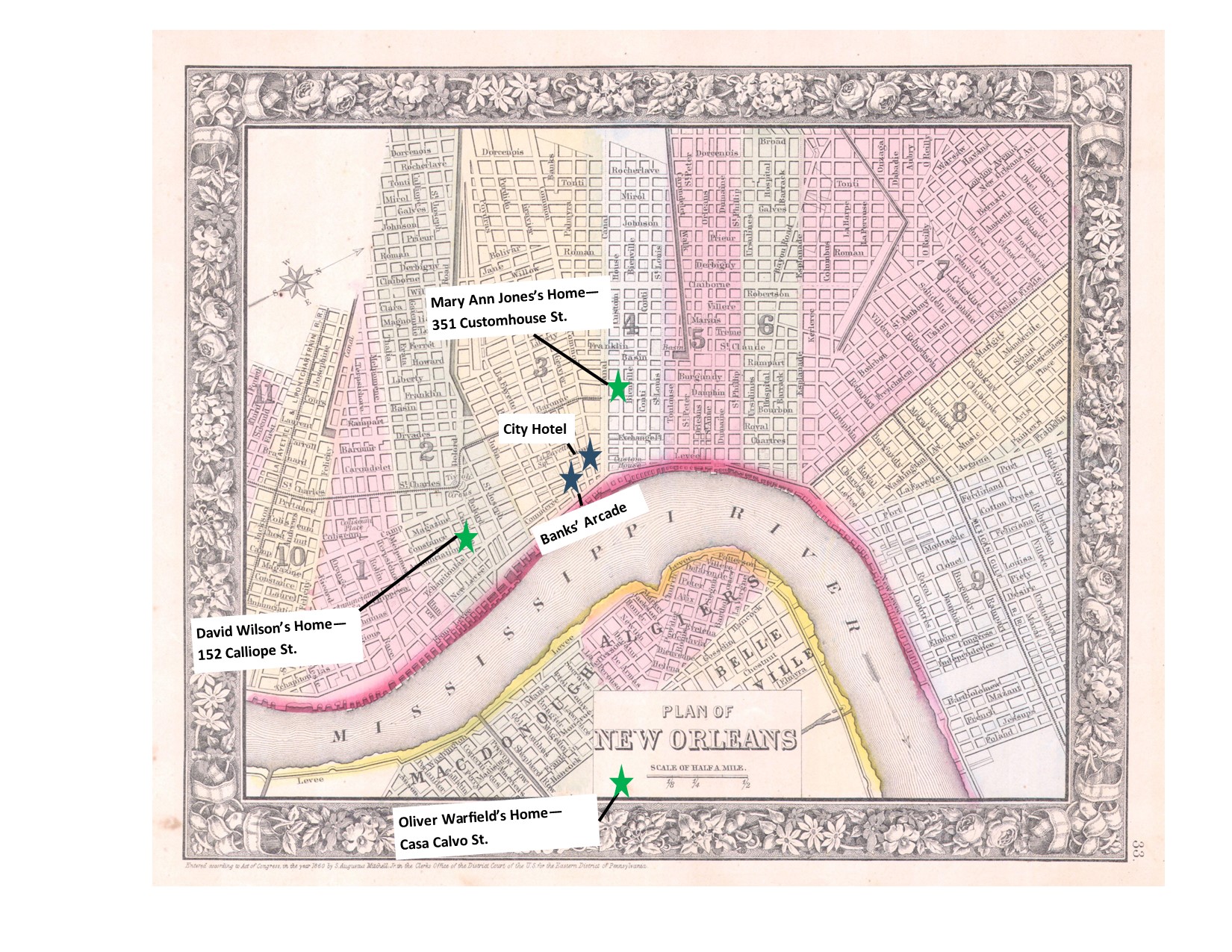

Born in Kentucky, David Wilson lived on Calliope Street in New Orleans between 1861-1880, and worked as a barber from roughly 1854-1890. Census records show us that David’s wife Winnie was born in Virginia, and lived with him from at least 1860-1880, and a woman named Sally Butler, possibly a widowed daughter or Winnie’s daughter from a previous marriage, worked as a housekeeper and lived in David’s home from around 1870-1880. David’s block of Calliope Street was in the Second Ward of the First District of New Orleans, and newspapers, primarily the New Orleans Republican, report David’s active involvement in the Second Ward Radical Republican Club, one of many of his memberships in civic organizations.

David arrived in New Orleans in 1835, likely having been forcibly removed from his birth state. In 1853, when he was 30 years old, he was enslaved by a man named William Wilson, a clerk (and later co-proprietor) for the St. Charles Hotel. William Wilson worked alongside Ruggles Morse as a clerk at the St. Charles, and in 1853, William sold David to Ruggles for $300. Ruggles Morse had a record for purchasing enslaved individuals from their enslavers and selling them back, either to the same person or to another close associate, after a year or two. By 1854, David had been sold back to William Wilson, who emancipated him on September 30th of that year. At this time, David had already begun working as a barber. Barbershops were a mainstay in luxury hotels, which may have been where David learned his trade. David appears to have been given, and/or chose to keep, the name Wilson as his own surname.

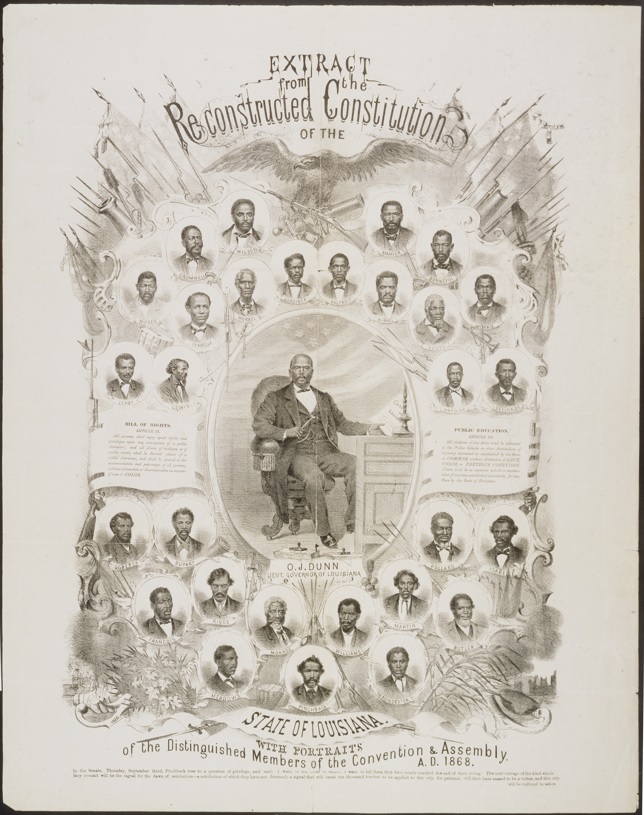

By the early 1860s, David was active in civic organizations and was a strong advocate for Black representation in local politics and public education. His connections with other prominent, politically active Black citizens in New Orleans such as C.C. Antoine, Solomon Moses, and future Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana Oscar J. Dunn grew when David was elected as a delegate to the State Constitutional Convention in 1867, representing New Orleans’s Second Ward. The Convention met to discuss Reconstruction in Louisiana and reform the State Constitution to reflect the rights of citizenship promised to Black individuals in the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution. David spoke and read frequently at these meetings, which were held from November 1867 through March 1868. The minutes of these conventions show that David was especially passionate about public education, advocating that all children “regardless of race, color, or previous condition [i.e., enslavement]” should have access to publicly-funded schooling up to age 21. David himself would have had limited resources available for schooling: it was illegal in the 1850s in New Orleans to teach a Black individual to read or write. Being a barber, however, likely would have opened David up to opportunities for self-education through community connections.

David’s portrait was included with other members of the convention, shown in the image to the right. David’s portrait is at the top, directly to the left of the eagle.

While it is not yet known when David passed away, he was active in local politics and organizations until at least 1892, when he and F.C. Antoine were sworn in as officers of the Damon Lodge No. 1 chapter of the Knights of Pythias. This fraternal group met at the corner of Camp and Common Streets – the same cross streets of the City Hotel, where David likely provided unpaid labor for Ruggles Morse decades earlier.

Extract from the Reconstructed Constitution of the State of Louisiana, with Portraits of the Distinguished Members of the Convention & Assembly, 1868

(Reproduced with permission from the Historic New Orleans Collection, object 1979.183)

Mary Ann Jones

From the antebellum period through the 1860s, free women of color in New Orleans had several avenues to employment and entrepreneurship open to them in ways that Black women in other states had not yet been granted. Not only did free Black women in New Orleans find work as laundresses, nannies, nurses, and housekeepers, more than 50% of properties owned by Black individuals in the city up to 1866 were owned by Black women, especially those who operated boarding houses. Boarding houses offered business travelers a simpler, more affordable alternative to luxury hotels, which catered to wealthy clientele and were more suited to stays of weeks or months at a time. As the Colored Conventions movement ramped up in the 1850s-1870s, Black men visiting the city for the conventions, at which Black citizens discussed at first abolition and later the rights to citizenship offered by the 14th Amendment to the US constitution, would often opt to stay at boarding houses, most of which were operated by free Black women.

Mary Ann Jones was one such entrepreneur. She operated a boarding house and lived on Customhouse Street (today Iberville Street) in the busy downtown area of New Orleans, an easy walk to and from the river ports and railroads. Her occupation in the 1861 and 1866 city directories identify this line of work as operating “furnished rooms.” This occupation also appears by Mary Ann’s name in the Register of Free Colored Persons Entitled to Remain in the State. These Registers were the result of an 1830 law enacted by white city officials in an effort to restrict Black citizens’ rights. Free Black individuals were required to register with the city to prove their free status as citizens born in the state of Louisiana (by providing birth or baptismal certificates, or papers showing their mother’s free status, as the status of children depended on the status of their mother), or proving that they were gainfully employed if they had been born out of state. Registration cost fifty cents. If a person could not pay, did not register, or could not prove their employment or born-free status, they risked expulsion from the state, imprisonment, and enslavement, even if their family had been free for generations.

Records show that Mary Ann had been enslaved by Olive Morse as the result of a sheriff’s sale purchase in 1849, with a man named Joseph Castanedo representing Olive on her account, but there are differing records as to how Mary Ann was emancipated. There is some confusion over this record, as Olive and Ruggles were not married until 1852, so the sheriff’s sale is part of Mary Ann’s history that we are still investigating. Additionally, there are discrepancies in the Register, as Mary Ann possibly appears in the Register twice. One record in the Register shows a Mary Ann freed in December 1854 by Mrs. O.R. Morse (i.e., Olive Ring Morse). Another shows the story we had uncovered prior to beginning our research in the Registers: that Mary Ann had been freed by her sister, Maria Martin, as the result of a court case.

Several Black individuals sued for their freedom or the freedom of loved ones in antebellum New Orleans. Many were successful. In 1855, Maria Martin hired the firm of Race & Foster to represent her in court. Her case was announced in English and French in an October issue of the Picayune, which indicated that Maria’s case was to “secure the emancipation, with privilege of remaining in the state” for both Mary Ann, around 40 at the time, and for a 19-year-old named James Ingraham, whose relationship to either Maria or Mary Ann is not yet known. We have not yet found further information about this case, but given the timing of the case and Mary Ann’s potential emancipation by Olive Morse, it’s possible that there were discrepancies and that ultimately the case was settled out of court, with Mary Ann gaining her freedom.

Both entries for Mary Ann in the Register show that she is around 40 at the time of registration, that her occupation is “furnished rooms,” that she, like Maria Martin, was born in Virginia, and that she stood at either 5’3” or 5’5”. We are continuing our research to determine if these entries do in fact refer to the same woman, or, if they represent two different women, if both of them were at one point enslaved by Olive Morse. We also hope to determine whether or not Mary Ann was one of the many women in her occupation who owned the building where she leased rooms.

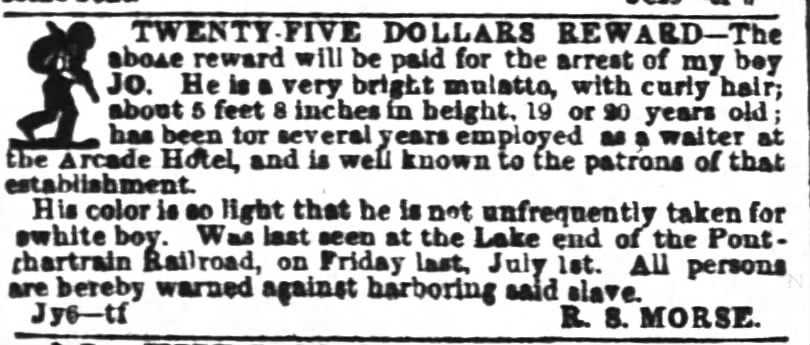

Joe

On July 1st, 1859, 19-year-old Joe was spotted in the town of Milneburg, LA (now part of New Orleans) at the Pontchartrain Railroad station, having escaped from his enslavement as a waiter at the Arcade Hotel on Magazine Street in New Orleans. It appears to be the last time he was in the New Orleans area. Those who sought to self-emancipate by running away from their enslavers took great risks: enslavers often placed advertisements in local papers offering rewards for arrests; if captured, time in jail and a return to enslavement was almost certain. Ruggles Morse placed one of these ads in the Daily Picayune from July 8th-28th, 1859 in search of Joe. However, research indicates that Joe may have been successful in escaping to freedom.

Joe was thirteen when enslaved by Morse, and would have been nineteen when seeking self-emancipation. Morse purchased several enslaved individuals in 1853, including three teenage boys who came to Morse through notorious slave trader Matilda Kendig Bushey: John, age 16, and Charles, age 15, were purchased by Morse on November 14th; Joe followed a week later on November 21st. Prior research had uncovered a newspaper article stating that the wait staff at the Arcade Hotel were entirely people of color, and the notice of Joe’s escape to freedom helps to corroborate this fact. It was also written of the Arcade’s dining halls that meals could be had “at almost all hours,” indicating that wait staff worked long days, or were called to service at patrons’ whims.

Joe, we learn from the Picayune notice, was around 5’8″ tall with curly hair, and was well-known as a waiter at the Arcade Hotel, which was under Ruggles Morse’s proprietorship. Joe had a light skin tone – according to Morse (who spelled his name “Jo”), “he is not unfrequently (sic) taken for a white boy.” While he may have risked a one-way ride on the Pontchartrain line from the Faubourg Marigny to Milneburg for 15 cents, Joe may also have chosen to leave New Orleans on foot, under the cover of the woods and swamps that the railroad ran alongside.

After nearly six years of waiting tables without pay, Joe’s self-emancipation was well timed. On June 1st, 1859, a month before Joe escaped to the railroad, a fire destroyed most of the Arcade Hotel’s dining room and a large part of the hotel itself. A smaller fire broke out in one of the Arcade shops on June 21st. The entire city of New Orleans was planning for Independence Day festivities by the end of June, and two slave auctions were set to be held in the Arcade on July 2nd, giving Joe ample opportunity to use the flurry of activity as a cover to slip away. Nearly two weeks after his escape, on July 12th, it was reported that due to the damage from the fire, the Arcade Hotel was to be torn down and replaced with a new building (this became the St. James Hotel, which opened in 1860 under Morse’s proprietorship). Morse’s business partner George Moore sold three other enslaved people on Morse’s behalf between July 20th-25th while Morse was out of town: Henry, age 20, on July 20th; John, age 22 (whom Morse had purchased a week before Joe), on July 21st; and Abraham, age 43, on July 25th. Abraham was sold back to his original enslaver, Catherine Digges Haney… the sister of Elias W. Digges, Morse’s predecessor as proprietor of the Arcade Hotel. It’s possible they intended to sell Joe to a new enslaver as well.

Joe likely succeeded in escaping the New Orleans area. His name did not appear among the arrests reported in the newspaper, and Morse did not seem to try to replace Joe, whose position no longer existed after the hotel was slated to be torn down. Given Joe’s description in Morse’s notice, it is not unlikely that he may have tried to pass for white as he sought a free life elsewhere, something that many other freedom seekers with mixed Black and white heritage opted to do during this time. Passing for white may have opened opportunities unavailable to those legally registered as Black in many parts of the country, such as passage on public transportation, employment opportunities, and options to own real estate or open a bank account.

Our paper trail runs dry for Joe after this, but his story is one of many showing the bravery and resilience of those who chose to liberate themselves from positions of enslavement and begin new lives.

Joe seeks freedom – from the Daily Picayune, July 8-28 1859

Notice in the Daily Picayune regarding Joe's escape to freedom, placed by Ruggles Morse from July 8-28, 1859.

Arcade Hotel New Orleans

Joe worked as a waiter, without pay, at the Arcade Hotel on Magazine Street in New Orleans, under Ruggles Morse's proprietorship.

Oliver Warfield

In 1865, Oliver Warfield was working as a deckhand and living on Casa Calvo Street in the Algiers district of New Orleans. In April of that year, the Picayune published a draft announcement for military service, and Oliver’s name was on the list. Given the timing of this draft, it’s likely that if Oliver served in the military, it would not have been for long, and he most likely would have fought for the Union, as New Orleans had been under Union occupation since 1862. Since he was familiar with maritime trades, it’s possible that he would have served in the navy.

Oliver’s emancipation is a part of his history that we are continuing to research. He would have been identified as a free man of color when the draft notice was published, but no city directories were published in New Orleans between the critical years of 1862-1865 when it was under occupation, so few written records exist that can help us fill in the gaps from those years. In April 1859, at the age of 20, Oliver had been enslaved by notorious slave trader Joseph Bruin and was forcibly brought to New Orleans, where he was purchased by Ruggles Morse. Oliver was enslaved by Morse, likely laboring in some capacity at the City Hotel, until 1860, when Morse sold him to Swedish immigrant Andrew Oliver Jackson, a stevedore who lived on Chartres Street. It was likely through Jackson that Oliver Warfield learned ship trades. When A.O. Jackson passed away in 1862, Oliver was one of the enslaved individuals listed in his succession papers – identified as property to be given to Jackson’s widow Mary Lee. Whether Mary emancipated Oliver herself or if Oliver was manumitted by Union occupation after 1862 is not yet known.

Oliver was most likely born in Maryland, and while research continues, records indicate that he may have been born free. His father or grandfather may have been Charles Warfield, a free man of color who appears on the Maryland census for 1840 listing an infant boy at home – Oliver was born ca. 1839. The 1850 census for Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania lists Oliver Warfield, 11 at the time, in the home of a wealthy white woman originally from Connecticut named Eliza Wright. Oliver is the only Black individual listed in the household, and is the same age as one of Eliza’s sons. Oliver’s birth state is listed as Maryland, and other than Eliza herself he is the only individual in the household indicated to have been born outside of Pennsylvania. In 1850, Pennsylvania was a free state, and Wilkes-Barre is around 125 miles overland away from New York City, where Joseph Bruin was known to ship out from. Bruin was based in Alexandria, Virginia, and had been one of the slave traders who enslaved and sold Black fugitives who had sought self-emancipation on the ship Pearl in an 1848 attempt to flee from Washington, DC to New Jersey. We do not yet know if Bruin or another slave trader captured and enslaved Oliver sometime before 1859, but it is likely that he was one of many free Black individuals who were forcibly removed from their home states and sold into enslavement. It is also possible that Oliver returned to Maryland after the conclusion of the Civil War. As we continue our research, we hope to discover more about Oliver’s life before he was brought to New Orleans, as well as after his emancipation.

Flora and her children Alonzo, Henry, and Hailly

Louisiana’s legal history is unlike that of any other US State, with the state and city judiciaries operating under civil law, rather than common law, a holdover from Spanish and French colonial rule. Laws in Louisiana sometimes worked in favor of Black citizens, particularly up until the 1840s when the population of New Orleans included thousands of free Black citizens working in multiple occupations, many of whom were entrepreneurs. White lawmakers made freedom more difficult for Black citizens to both obtain and maintain throughout the 1850s as war was looming. Under civil law, children of enslaved Black mothers were required to remain with their mother until the age of ten. The status of the mother, free or enslaved, would be passed on to her children, regardless of their father’s status. If an enslaved Black mother was sold from one enslaver to another, her children went with her up to the age of nine, but the family remaining together was not guaranteed unless their new enslaver purchased her children as individuals. If an enslaved child was not purchased as an individual, they would be sent back to their original enslaver once they turned ten.

This law would have weighed heavily on at least three women who were enslaved by Ruggles Morse: Louise, whose son Jim was six years old in April 1848; Hagar, whose son Jefferson was seven in May 1848; and Flora, whose children Alonzo, Henry, and Hailly were ages nine, seven, and four respectively in May 1859. Flora, Alonzo, Henry, and Hailly were enslaved by Morse, likely at the City Hotel, for a very short period of time – a little over a month. Morse tended to do business with people he was already associated with, either in the hotel business or other ventures, including the pharmaceutical firm of E.B. Wheelock & Co. It was Wheelock who first enslaved Flora and her children in Louisiana, and it was another of Morse’s business partners, C.E. Girardey, who tried to sell Flora, Alonzo, Henry, and Hailly in an 1859 auction in the lobby of the City Hotel. Though the auction occurred in March, the enslaved family was not sold until May, when Wheelock, acting as Morse’s agent, sold them to a man named John O’Neill. It is possible that during the short few weeks that her family was enslaved at the City Hotel, Flora provided unpaid labor for Morse – she is described as “a good cook, washer, and ironer,” and likely would have worked in the kitchen or laundry room of the hotel.

During the antebellum and war period, and rippling out through the later 19th century, white businessmen, slave traders, and lawmakers invented racial descriptors for nonwhite enslaved individuals – Black and Indigenous – based on their parentage or assumed heritage. Girardey described Flora, Alonzo, Henry, and Hailly as Black, indicating that the children’s father was also Black – had he been white or mixed-race, the children would more likely have been described differently at the time. We do not yet know the identity of their father, or if Flora considered him to be her husband. We also do not yet know if the family became separated in any way after Alonzo turned ten, or if any members of the family tried to reconnect after the war by placing Lost Friends advertisements in the paper. The story of Flora and her family is one that we hope to piece together further as our research continues.

Commitment to Ongoing Research & Interpretation

The Unwilling Architects is an ongoing initiative, and Victoria Mansion is committed to continuous research beyond the life of the primary grant period. Source availability is constantly evolving, and our interpretive materials and research are living, intentionally designed and presented to change as more information is uncovered.

For this beginning phase of the initiative, we have been indebted to the primary sources that have been available to us through online repositories. With little to no extant material culture that may have related to the individuals we are researching as part of this initiative, objects such as hotel manuals and tools that might have been used by people performing similar labor to those enslaved in Morse’s hotels might also provide helpful future interpretive methods.

We encourage you to continue checking on this page, as well as following updates on our Blog. It is our hope to learn more about all of these individuals in order to interpret as much of their lives as we can with the documentation available to us, and will continue to update this page and our Blog with new information as it comes to light.