Western culture began defining itself in contrast to the East as early as the Trojan War of Greek versus Persian. In the centuries to follow, as European civilization advanced, its soldiers, traders, adventurers, and artists increasingly perceived the East as a nostalgic counterpart to progress. Across much of the second millennium, Europe conceived of the regions from Egypt to Turkey to India and, eventually, to China and Japan as places to be studied, traveled, occupied, commodified, and poeticized.

After World War Two, as empires fragmented and the new field of postcolonial studies arose, scholars in both hemispheres gave a name—“Orientalism”—to the West’s fascination with Eastern cultures. They showed how this fixation often resulted in stereotypes of the “Oriental” character and “exotic” lifestyle.

Today, artists take care not to reproduce stereotypes when depicting cultures not their own. In contrast, artists of earlier periods deliberately sought to reproduce the most typical aspects of a time and place, whether in paintings, objects, architecture, or decor. Striving to reveal the essence of a region’s character, they both celebrated and sensationalized the novelty of foreign lands to captivate audiences. Nineteenth-century male painters, for instance, found an excuse for painting female nudity in depictions of harems they would never have been allowed to enter.

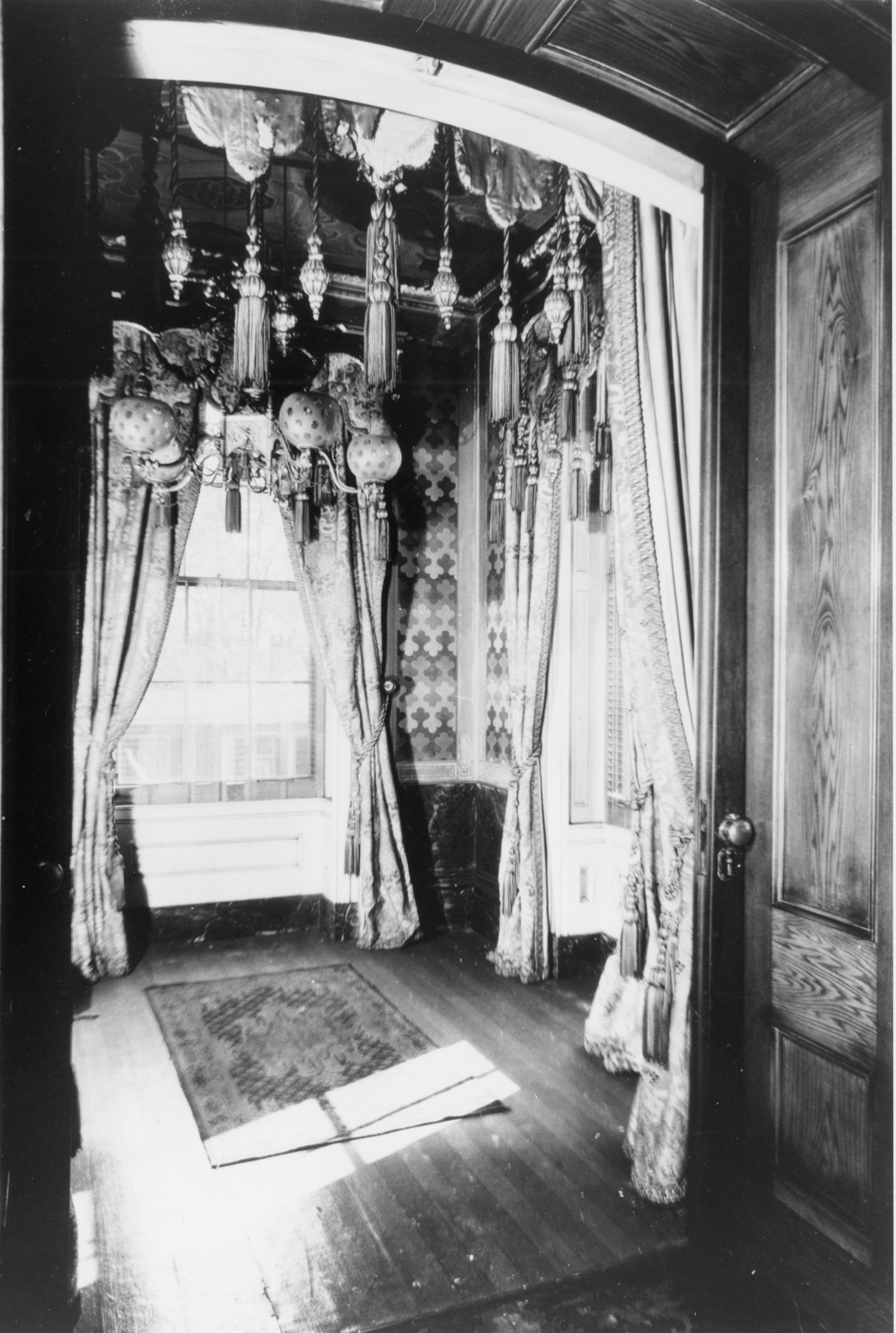

Reproducing impressions of the East was not the sole purview of painters. “Like Orientalist subjects in nineteenth-century painting,” writes Sara J. Oshinsky, “exoticism in the decorative arts and interior decoration was associated with fantasies of opulence and ‘barbaric splendor.’” Indeed, as a gorgeous example of 19th-century Orientalism, Victoria Mansion’s Turkish smoking room faithfully evokes facets of Islamic interiors while fabricating a dream of luxurious male repose.

Postcolonial studies have firmly established the connection between Orientalism and Europe’s exploitation of Eastern lands and resources. It is important to acknowledge, however, that for millennia cultural exchange between the two hemispheres has flowed in both directions. In fact, like the concept of Victoria Mansion itself, aspects of Oriental décor originated in ancient Rome.

It was the Romans who “invented” the villa, a house situated either outside the city limits or within an urban enclosure (Bezemer Sellers and Taylor). The villa offered psychic restoration to sophisticates exhausted by the whirlwind of business and pleasure in the metropolis. Ornamented with statuary and wall paintings “relating to entertainment or to mythology,” like Victoria Mansion’s rustic musicians and contemplative nymphs, the Roman villa spoke to the owners’ wealth and taste (Lockey). A perfect frame for the Morses’ summer hiatus from the pressure of managing great hotels, the villa provided “an idyllic setting for . . . withdrawal into a domestic retreat from the city” (Bezemer Sellers and Taylor).

But it was the public bath, an urban institution, that captivated the Eastern inhabitants of Rome’s Mediterranean empire. “Byzantine baths,” writes Elizabeth Williams, “kept many of the same traditions of the earlier Roman baths, including trends in decoration such as intricate mosaic floors.” It is, indeed, a short distance down the hallway of Roman history from Victoria Mansion’s delightful Pompeian tub room to the Turkish smoking room!

Visitors to the smoking room will immediately notice that it possesses the only painted surfaces in the house devoid of putti, maidens, scenic landscapes, or animals. The vibrant red, green, and gold calligraphic and geometric ornamentation follows the non-figurative tradition of Islamic design. Yet even these motifs may be traced back to Greece and Rome. According to The Met’s Department of Islamic Art, “Islamic artists appropriated key elements from the classical tradition, then complicated and elaborated upon them in order to invent a new form of decoration that stressed the importance of unity and order.” Aha! The Greek key design in the tub room evolves into the lattice motif of the smoking room.

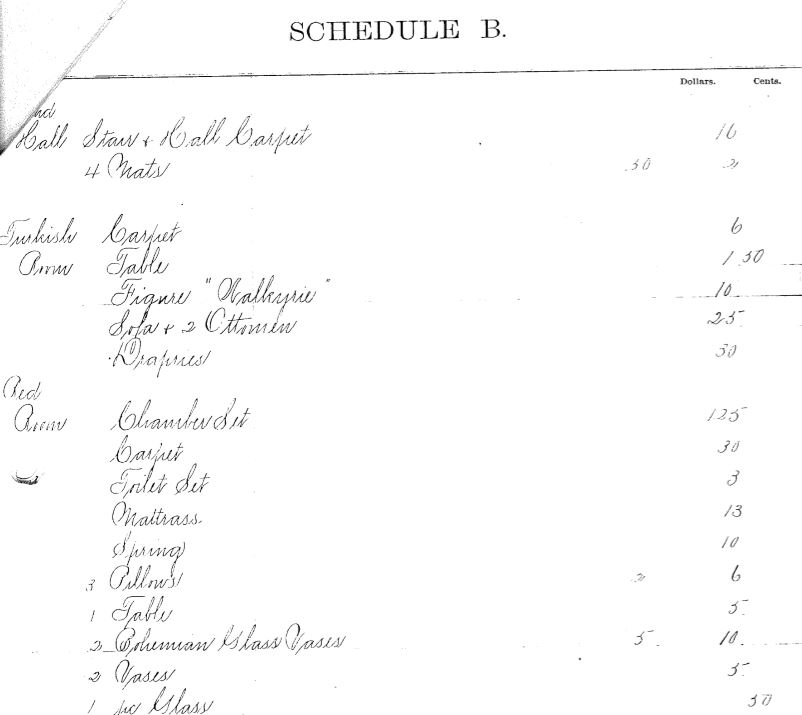

This genealogy in no way diminishes the exquisiteness of Islamic art, but does illuminate the underlying cohesiveness that is palpable throughout Victoria Mansion, in spite of its seeming eclecticism. Perhaps the Roman connection could even make sense of a detail that seems incongruous from today’s perspective: the sculpture of a nymph in the Turkish smoking room. But this nymph, it turns out, is a replacement for an earlier lost statue, described in Olive Morse’s 1893 inventory of the smoking room as a “’Valkyrie’ figure.” It’s intriguing to ponder Ruggles Morse’s choice of this militant female companion for his leisure hours.

The Mansion’s original program of wall-to-wall carpeting throughout much of the house provides yet another historical connection between Eastern and Western décor. Long linked with the Persian empire, intricately woven carpets connote opulence and wealth, for only the rich can afford “an expensive textile underfoot” (Denny). The invention of pile carpets, with their lush texture and complex patterns, was perhaps one of the earliest gifts of the Persians to the Romans—and back again! Providing evidence of continuous exchange across the borders of empire, scholars have found that a “Turkish carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck’s Paele Madonna painting was traced back to late Roman origins” (Brüggemann).

Victoria Mansion’s Roman and Islamic influences were ahead of their time for private homes in mid-nineteenth-century America, but foretold trends to come. The world was shrinking, and popular international exhibitions in major European capitals exposed the public—including, no doubt, the Mansion’s German-born interior designer, Gustave Herter—to illustrations of new discoveries at Pompeii and to commodities from the Islamic world. Fortunately for Ruggles Morse and today’s visitors to the Mansion, the “complexities of geometric design associated with Islamic decorative arts and architecture became a source of inspiration” to the ingenious Herter and his generation of master craftsmen (Oshinsky).

Works Cited

Bezemer Sellers, Vanessa, and Geoffrey Taylor. “The Idea and Invention of the Villa.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Brüggemann, Werner. Der Orientteppich/The Oriental Carpet. 1st ed. Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2007. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persian_carpet.

Denny, Walter. “Islamic Carpets in European Paintings.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Department of Islamic Art. “Geometric Patterns in Islamic Art.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/geom/hd_geom.htm.

Gontar, Cybele. “Neoclassicism.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Kenney, Ellen. “The Damascus Room.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History,. The Metropolitan

Lockey, Ian. “Roman Housing.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Meagher, Jennifer. “Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Oshinsky, Sara J. “Exoticism in the Decorative Arts.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.

Williams, Elizabeth. “Baths and Bathing Culture in the Middle East: The Hammam.” Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/.