Pudgy, Pouty Putti

July 25, 2019

By VM Guide Charisse Gendron

In early 1998, Victoria Mansion started preparations for an exciting project: the reconstruction of its large stained-glass skylight, which had been shattered in a storm sixty years before. Surviving pieces were salvaged at the time, but only one clue remained to the overall composition: a roundel bearing a winged putto personifying the season of Spring. This roundel was known to be one of a set of four, but the others were destroyed during the storm incident, and no documentation of their imagery existed. Overseeing the project from concept through completion, former Curator Arlene Palmer Schwind strove to ensure that the reproduction skylight would be as faithful as possible to the original.

Denys Peter Myers, an architectural historian who had visited the house in 1933, was contacted to see what he remembered of the missing roundels. Myers wrote that he was vague on the details, but had the impression that the four putti differed in their poses, attributes, and color schemes.* As he pointed out, the ingenious Gustave Herter, who designed the Mansion’s interior and oversaw the creation of the skylight, would have settled for nothing less than inventive variety. This was helpful, but prototypes on which to base the new roundels were elusive. In research for historical examples of personifications of the seasons, the Mansion recruited an artist steeped in typology, Canadian Ron Whate, to assist in the search and make sketches for the new putti.

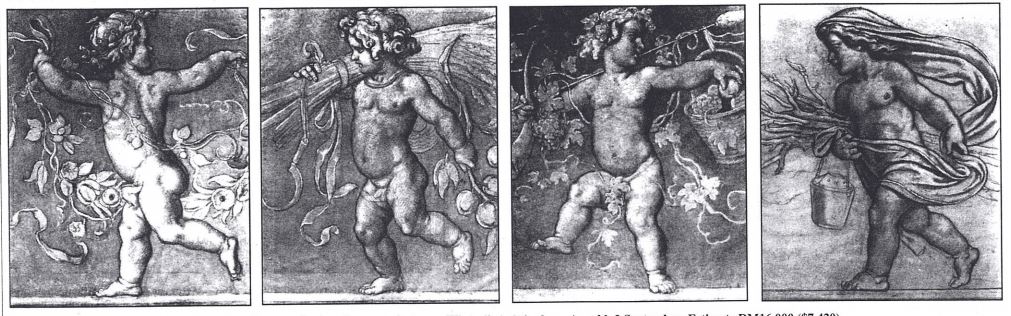

Examples from the Renaissance to the mid-nineteenth century were studied, from Raphael, whose putti influenced Giuseppe Guidicini’s frescoes in Victoria Mansion’s Parlor, to Enrico Franciolli’s paintings of ladies and putti stepping gracefully in a circle on the ceiling of Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater. A windfall was the discovery of Austrian illustrator Moritz von Schwind’s Allegories of the Four Seasons, depicting sturdy, curly-headed youths carrying elaborate attributes: a garland of flowers for Spring, a sheaf of grain and a peach tree branch for Summer, a grapevine and fruit basket for Autumn, and kindling and a pail of embers for Winter. The only problem was that the figures had no wings. As Arlene Schwind noted in a humorous communication referencing von Scwind’s images, “Unfortunately, these dudes are not flying.”

And yes, these are dudes, made evident by Summer’s full frontal nudity. His pose is somewhat unusual for putti of his day, whose sex is often shrouded by the positioning of thighs, shadows, and drapery. Partly this is due to the puritanism of the nineteenth century and partly, perhaps, to the confusion of putti with cherubs, who, according to Christian doctrine, have no sex. (Even the faithful admit that humans, from the beginning, were sexual creatures, but as late as 1969 parishioners complained about Ron Whate’s mural of a naked Adam and Eve for their church. In response, the artist “carefully drew in some fruit for Adam and some leaves for Eve,” reported the Toronto Star.)**

Confusion as to the ontological status of putti can be placed at the doorstep of Renaissance artists, who first conflated the iconography of cupids and cherubs. In ancient times, Cupid was depicted as a winged youth who carried out the whims of his mother, Venus, the goddess of sexual love. In medieval art, cherubim were also portrayed as winged youths, but their role was to enforce God’s laws. During the Renaissance, both cupids and cherubs were often recast as winged human babies, younger, plumper, and less dire than their forebears. They could be distinguished from each other only by their profane or sacred context. A putto, from the Latin word putus, meaning “boy,” is a fusion of the two, sometimes puckish, sometimes dreamy, and often removed from any context at all, bespeaking only the Renaissance artist’s joy in painting rounded flesh. As such, they are less symbols than ornaments.

In contrast, Moritz von Schwind intended his putti, with their detailed attributes, as “allegories” of what a folklorist might call the ur-myth of European culture, based on the cycles of nature. As explained by the critic Northrop Frye in his influential Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays,*** each season is a distinct manifestation of this myth: spring signifies birth; summer, triumph and harmony; autumn, decay and separation; and winter, chaos and death. Going back even further, the ancients linked the seasons to the “humors,” or temperaments. Spring corresponded with the sanguine or optimistic humor; summer, the choleric or volatile; autumn, the melancholic; and winter, the phlegmatic or calm. The traditional attributes of flowers, grain, grapes, and embers are keys to the unlocking of the myth.

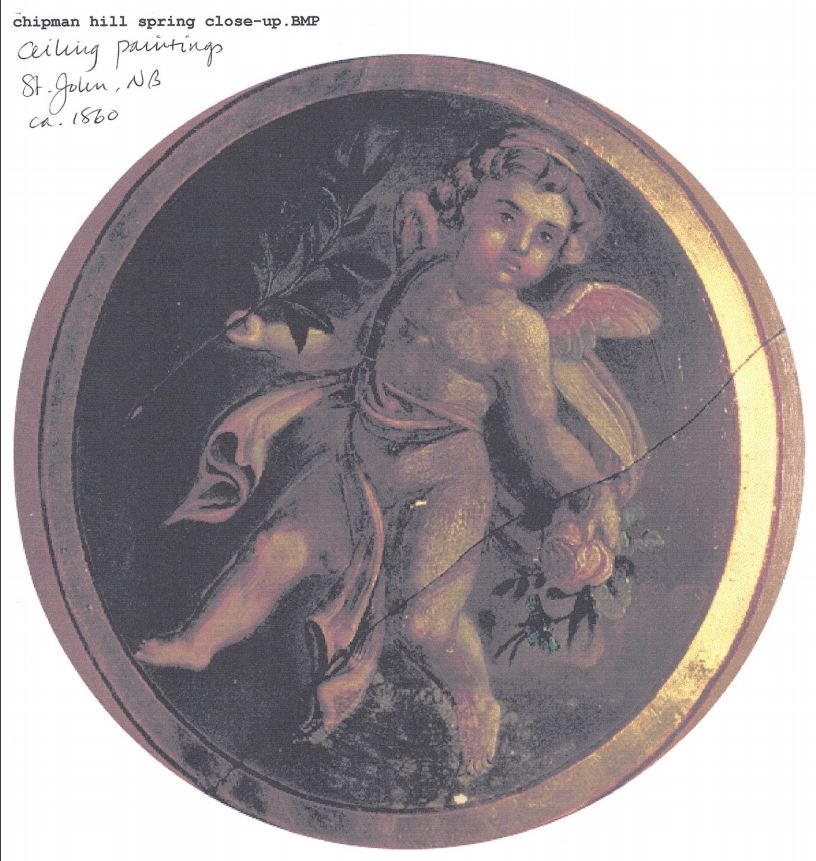

Following the discovery of the von Schwind illustrations, Ron Whate’s research turned up a final important antecedent for the Mansion’s putti: a set of seasons in a mid-century home in the historic Chipman Hill district of Saint John, New Brunswick. Its original owner, James Moran, was a prosperous ship builder who “doubtlessly had dealing in Portland and area,” Whate wrote excitedly to Schwind, suggesting that some swapping of interior design concepts—or perhaps even artists—might have occurred between Moran and Ruggles Morse. The description of Moran’s ceilings would sound familiar to visitors to Victoria Mansion:

paintings . . . shaded to give a three-dimensional effect [of] plaster mouldings . . . roundels in each of the four corners . . . large, central, gilt-trimmed medallion trompe l’oeil paintings . . . polychromatic Cupids . . . panels of leaf scrolls and flowers suggesting three-dimensional plasterwork touched with gilt. . . ****

Connections between the houses have not been able to be confirmed, but the Chipman Hill images nonetheless made a good match with the Victorian Mansion’s Spring. The artists of both houses worked in a style somewhat cruder than that of Moritz von Schwind. Their attributes are simpler and their figures less refined. As Whate pointed out in an email at the time, the legs of Spring would be awkwardly positioned if not camouflaged by drapery.

The search for prototypes had been successfully concluded. Whate, Schwind, former director of Victoria Mansion Robert Wolterstorff, and stained-glass consultant Robin Neely settled on attributes for the missing seasons: a sheaf of wheat and sickle for Summer; grapes and a thyrsus (the staff carried by Bacchus and his followers) for Autumn; and a pot of coals for Winter (a torch was ruled out as an ancient symbol of marriage, not to mention the Olympics). Working from his disparate sources, Whate submitted three sets of drawings for the missing roundels in mid-November 2000. As his concept came together, he reported, “The faces are all different but still [have] that same pudgy, pouty look.”

In February 2001, the final designs were delivered to Gene Mallard, a stained-glass artist under Neely’s direction, who finished the project on deadline. The complete sequence of the seasons was revealed at a Skylight Gala Celebration on April 28. At last, nature was whole again—at least in the gloriously artificial universe of Ruggles Morse.

Sources

*Correspondence referenced in this article is in the archives of Victoria Mansion.

** https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-TSPA_0104269F&R=DC-TSPA_0104269F.

***Princeton University Press, 1957.

**** https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=199.